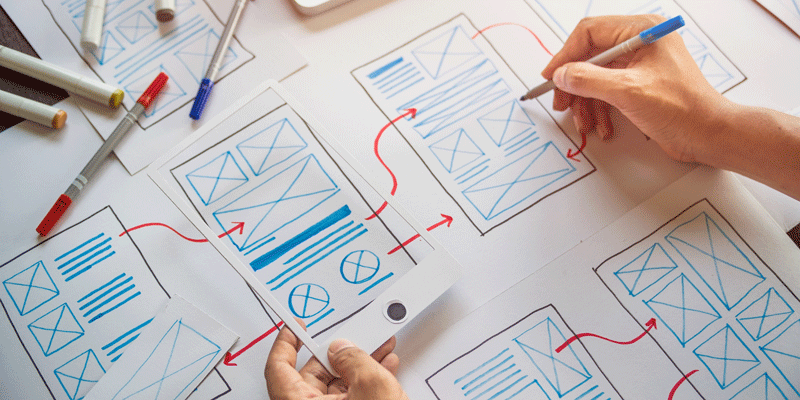

Prototypes are a great way to get customer feedback about elements of your proposed innovation before you have to invest a ton of resources in them. But there is a bit of science to how you draw the lessons a prototype can teach you.

Prototyping is an integral part of the design thinking process. Mocking up a web page, making models, giving customers something that helps them understand what you are trying to accomplish and the like are invaluable as part of a smart innovation program. After all, if you can prove that an idea won’t work when you’ve spent $100 to create a prototype, it’s a lot less painful to go in a different direction than when you’ve spent a million! And don’t fall into the trap of thinking that just because funds are plentiful you don’t need to test your hypotheses before going full on product launch (see disastrous launch of Quibi). So how do we make sure that we are learning the right lessons from our customer tests?

Lesson 1: Believe in the vision but be willing to shift your approach

As Safi Bahcall, the author of a terrific book Loonshots says, the first law of Loonshots is to “expect three deaths.” What he means by that is that truly revolutionary, paradigm-shifting concepts are often ridiculed in their early stages. That doesn’t mean they are bad concepts, but it might well mean that the world isn’t quite ready for them yet.

For example, Jeff Hawkins, one inventor of the original Palm Pilot device – a device that was less than a computer but more than a phone at the time – had lived through one disaster after another before hitting the formula that eventually changed the world. He’d designed one of the first handheld computers, the GRiDPad a decade previously. It was an engineering marvel, but too big for people to casually carry around. He’d also seen other devices – the Newton the Zoomer and others – fail. Eventually, spurred by the conviction that such a device could be useful if it were small enough, he carved up a block of wood to fit his shirt pocket. As he went through his day, he’d observe all the times when such a device could be consulted for sending messages, making appointments, keeping notes, that sort of thing. Convinced that if they could get the size right, the idea had potential, he persisted by rejecting all kinds of proposals to put more stuff in the device. Eventually, the Palm Pilot was sold as a complement to the PC – “The connected organizer that keeps you in touch with your PC.” It proved a hit, setting the stage for generations of similar devices and the form factor that persists even in smart phones today.

The lesson here is to get to the root of why something doesn’t work without losing your enthusiasm for the vision of how good it could be. As Safi points out, in the early stages such efforts are “fragile” and need to be nurtured.

Lesson 2: Mind the false fails

This is Safi’s second law of moonshots, which gets at really understanding the “why” of why a prototype or experiment didn’t work. He cites the example of investors being skeptical of Facebook in its early days because so many users had abandoned the social networks that came before it – SixDegrees, StumbleUpon, Friendster, Bebo and so on. Peter Thiel, an early Facebook investor however, dug beneath the surface of user behavior to discover that the Friendster site was a hot mess. It crashed frequently, had a horrible interface, went down a lot….and yet, users stuck with it, lured by the network effects of having connection on the site. The problem, Thiel concluded, wasn’t that social networks weren’t sticky. The problem was that the technology was terrible and didn’t scale. He put a big investment in Facebook and as they say, the rest is history.

So when you get negative feedback about your prototype, it’s super important to make sure that you are not mis-attributing the result to something that may not be a core feature of what you’re trying to do.

Here’s one I was personally involved with. Way back in the day, I was involved with the design team for a company called Greenwich Pharmaceuticals. They had come up with a drug for severe rheumatoid arthritis that was very safe, since it was based on carbohydrates and appeared efficacious for very severely impaired patients. Patients in the clinical trials reported that it was life-changing for them!

But in a “perils of Pauline” series of events, the drug eventually never made it to FDA approval. Here was the thing, though: it performed as well for patients as existing treatments (typically anti-inflammatory drugs). But in a critical final set of trials, it didn’t perform sufficiently better than the placebo for the FDA to grant it approval. We were devastated.

In trying to disentangle what happened, it dawned on us that there was a lot more going on with these patients than the effects of the drug. During the clinical trial, the people (primarily elderly) taking it (or a placebo) went to the doctor every two weeks. While they were there, they got to swap symptoms with the other patients in the waiting room, got sympathetic conversations with the nurses, and were checked for adherence to other medications. In other words, they were getting surround-sound medical care for everything bothering them, which we believe swamped even what we felt was the very good efficacy of our drug. Unfortunately, this realization came too late to redesign the clinical trial protocol.

Greenwich Pharmaceuticals went out of business, but Ed Thompson, the charismatic founder and lead cheerleader, rescued the assets of the company to found Pharmaceutical Medical Research Services (PMRS) which became a big success. For a blast from the past view of PMRS, check out this video.

Lesson 3: Create a safe space to explore the “why?”

If your venture is not making progress, or not making progress as fast as some people think it should, the bureaucracy is more than happy to squash it. What you need, in these cases, is a place that offers some resources, the opportunity to continue to learn and a propensity to “tinker.” As Alberto Savoia expressed to me, “great companies tinker a lot.”

What “tinkering” does is it allows you to design experiments that can get you closer to the end point by finding out what doesn’t work so that you can find out what might.

Inventor James Dyson, for example, was famous for tinkering. He reportedly went through 5,127 prototypes of his bagless vacuum cleaner before finding the one that could be commercially viable. It’s a great prototyping story. As he told Inc Magazine:

I’d purchased what claimed to be the most powerful vacuum cleaner. But it was essentially useless. Rather than sucking up the dirt, it pushed it around the room. I’d seen an industrial sawmill, which uses something called a cyclonic separator to remove dust from the air. I thought the same principle of separation might work on a vacuum cleaner. I rigged up a quick prototype, and it did.

Dyson’s multibillion dollar company reflects the philosophy that getting to market is not necessarily the most important outcome for an investment in invention or R&D. Sometimes a prototype helps you learn about something that would otherwise never be discovered.

Lesson 4: Find a Sherpa

I’m often asked about what leadership roles are necessary in guiding innovation. I think there are at least three, although they are often performed by multiple people at multiple levels. The first is of the executive leader. This person sets the strategy, makes it clear what kinds of ideas and innovations fit, creates resource flows and fosters alignment among the senior team(s) about the importance of the innovation agenda.

At the level of a given venture or project, we have the internal entrepreneurs. These are often the energetic, passionate, love-the-idea-beyond-anything-else people with the energy to persist despite setbacks and to break through obstacles. They are also quite often very difficult for large organizations to cope with. They don’t want to come to the Thursday update meeting. They have no interest in whether their ratio of senior to junior people conforms to HR’s requirements. They fly pirate flags and are on a mission, dammit!

So what you also desperately need to get the most benefit from prototypes is a character I call the Sherpa. Like the Sherpa who is going to help you climb Mt. Everest, the organizational Sherpa knows what it means when the organizational wind blows one way or another, who can trade favors, who has friends across the organization and who has significant senior-level credibility. At IBM during the Lou Gerstner era, they actually baked the concept of a Sherpa into their innovation structures by pulling senior people out of their roles and giving them the responsibility to nurture new ventures. Sherpas provide political air cover, resources, and the ability to tap into multiple revenue streams as groundbreaking innovations lurch along through the prototype process.

Lesson 5: Tailor Your Prototyping Strategy to Your Goals

This terrific article by Jason Lichtman, now at Autodesk, offers some non-obvious ways to make sure your prototyping strategy matches your goals. You might, for example, choose to spend a little more than the bare necessity if it will compress total project time. You should be absolutely clear on what you hope to learn during each phase of the prototyping process. You might incorporate different design elements in a single prototype to limit the number of models you need to build. You might change the scale – rather than building a full-size prototype, perhaps try a half-scale model. Remembering that your prototype contains any number of assumptions about the relationship among elements in it, test out a lot of different combinations before attributing success or failure. And remember, sometimes making things by hand (like blocks of wood to test for size) can teach you more than using fancy technologies.

** Content originally published by Thought Sparks **

Most Recent Posts

Explore the latest innovation insights and trends with our recent blog posts.