In the spring of 2019, the TIM Foundation was contacted by the Dutch national government requesting if TIM Foundation would be willing to cooperate in setting up an innovation maturity model for the central Dutch government. TIM Foundation already possessed such a reference model that had been developed over the past 14 years in cooperation with the PDMA – the Product Development and Management Association, an international association of innovation managers and product developers. After discussing the outlines of this new model, there appeared to be a good match between what the central government needed, and what St TIM Foundation could bring to the table in terms of expertise and content material, having a starting position with this initiative. That outcome led to a multi-year collaboration that is detailed in this article.

Why is innovation often more difficult in government than in companies?

First of all, in the field of innovation management, it is necessary to explain why it is still very difficult to achieve innovation within public services in many cases. A good number of factors have been found, which can explain this phenomenon in whole or sometimes in part. We list the most important ones:

1. Government bodies and not-for-profits have quite a few rather disparate roles in driving, initiating and implementing innovations, which are not always clearly separated:

- It can act as an investor in innovative projects with a public benefit. For example, in large infrastructure such as e.g. innovative dams, locks, fish tidal rivers, digital identification, etc.) involving innovation, because they are, for example, large, unique or one-off in nature (Eastern Scheldt storm surge barrier), or highly innovative in nature, such as the development of space technology.

- It may act in the role as a product/service developer for its own government services to citizens or business (e.g. a new passport, driving licence, DigID, etc. )

- It can be a facilitator and driver of innovation for companies and not-for-profits. Then it acts as a networking organisation, i.e. a linking, facilitating party to connect innovation partners, or stimulate innovations through investment schemes.

- But it can also act as a market master: it must quite often make laws and regulations that can strongly influence the development of innovations, both nationally and at European level. (Think e.g. pharma/biotech drug approval, food safety regulations, market regulation).

Clearly, for each of these separate roles, the function and actions of government and the rules of the game under which it must operate are quite different, and different dynamics come into play. Yet there are a few more characteristics that add significantly to the complexity:

2. There are a lot of stakeholders to be served by governments, and their interests are in most cases very diverse, and regularly downright contradictory. All these parties compete for attention and priority. A simple example is, for instance, innovations in the field of sustainability: in the case of newly constructed wind farms, parties are sometimes diametrically opposed to each other (citizens versus energy companies), while the sustainability transition requires society, and thus the government, to take firm steps towards stimulating the development of renewable energy sources. For companies, conflicting interests are often much less prominent.

3. The public nature of government or institutions means that they operate in the focal point of media attention in the broadest sense of the word. Every mistake made, cost overrun or transgression of its own regulations is followed with close attention, and also published extensively via press and social media. This happens quite rarely with companies, although it is quite obvious that things can go wrong very regularly too, and very expensive mistakes are made while innovating. Simply because the government is supposed to operate ‘fail-proof’, there is very little to no room or tolerance for mistakes in its main processes. Therein lies a major problem. In fact, being allowed to make mistakes is an essential part of innovation: many innovations fail initially and only when learning effects have occurred through repeated failure do they eventually lead to success. When an organisation is expected to operate flawlessly, not only is there no room for failure, but there is often no learning and hence no innovation. An organisation that is not allowed to fail (somewhat controlled) from time to time learns nothing at all. Worse, it can lead to great convulsiveness, to covering up, to hedging – in short, unproductive behaviour. Incidentally, when governments make mistakes, the mistakes can have a very big impact on citizens and businesses.

4. Another factor that regularly causes additional complications is the fact that the political-administrative system often causes ongoing discussions on major changes of course in the interim, which does not sit well with important innovations. Examples of these are the long-term implementation of large ICT systems, the execution of major projects or the construction of new physical or digital infrastructure, for instance. Having to change course half-way is then a major risk, both in terms of costs and time. Let us not forget that every 4 years a new political landscape is caused by new elections.

5. The scale at which the central government in particular operates as an organisation is also extraordinarily large. In addition, the organisational structures and social missions of its constituent parts are very diverse. The highly diverse societal missions that the government faces in all its sections, on the contrary, demand a great multidisciplinarity of organisational parts, and requires intensive cooperation between government institutions that until now could operate rather autonomously. Particularly when faced with so-called wicked problems. For example, look at what is happening in the field of sustainability, where in the Netherlands at least four ministries are actively involved and a number of others around them. This organisational setup could lead to delays, confusion and diffuse leadership. Recently appointed ‘case’ ministers for climate and energy, digitalisation and nitrogen are examples of attempts to resolve deadlock.

6. Expectations are also regularly created which, it turns out, can only be partially or not at all met afterwards. Internal causes of falling short of those expectations can often be traced to some root cause or combination of causes such as:

- Culture: perception of risk differs between employees and organisational units, learning ability is not always very high

- Frequent leadership changes and related strategy changes can severely hamper progress on long-term objectives. After all: before a long-term objective is or can be achieved, changes have already taken place and a new course has to be set.

- Solid bottlenecks to good innovation policy are also regularly observed in culture, structure, processes, talents and leadership within central government, which actually need to be addressed first if innovations are to have a chance of success.

In summary, innovation policy in government and not-for-profits is multifaceted and extremely complex, actually much more complex than innovation in companies. This complexity is not only frequently misunderstood or underestimated, but it is often subsequently difficult to create the right conditions under which success with innovation becomes possible at all.

Keep in mind that the solid transition tasks facing public institutions not only require effective internal innovation-oriented leadership, but also external innovation-oriented leadership towards stakeholders, and innovation in the management of the organisation.

Why do you actually need to innovate, and why do we actually need to improve our innovation skills?

This is a very good question indeed. In a very large and diverse organisation like e.g. a central government, wanting to increase innovation capacity is a task in itself, and that in an organisation that already has many challenges with regards to innovation. In the present day, societal pressure to come up with innovations is very high, criticism from society is also mounting, as tech giants have a faster pace, often difficult to match by governments or institutions. Tech giants could go much further in their development efforts and have little patience. Additionally, they are now often more powerful than those governments themselves. Social problems in the areas of economy, security, welfare, education, inequality, poverty, housing shortage, delays in digital transformation, energy transition, environmental issues, healthcare costs, etc. have been piling up in recent years. Calls for robust change and interventions from the government are increasing hand over fist.

In these cases, particularly (but not exclusively limited to) the central government is facing large, transformational social tasks that will require a transition from both its own organisation and society, and which even easily exceeds its own current span and scope.

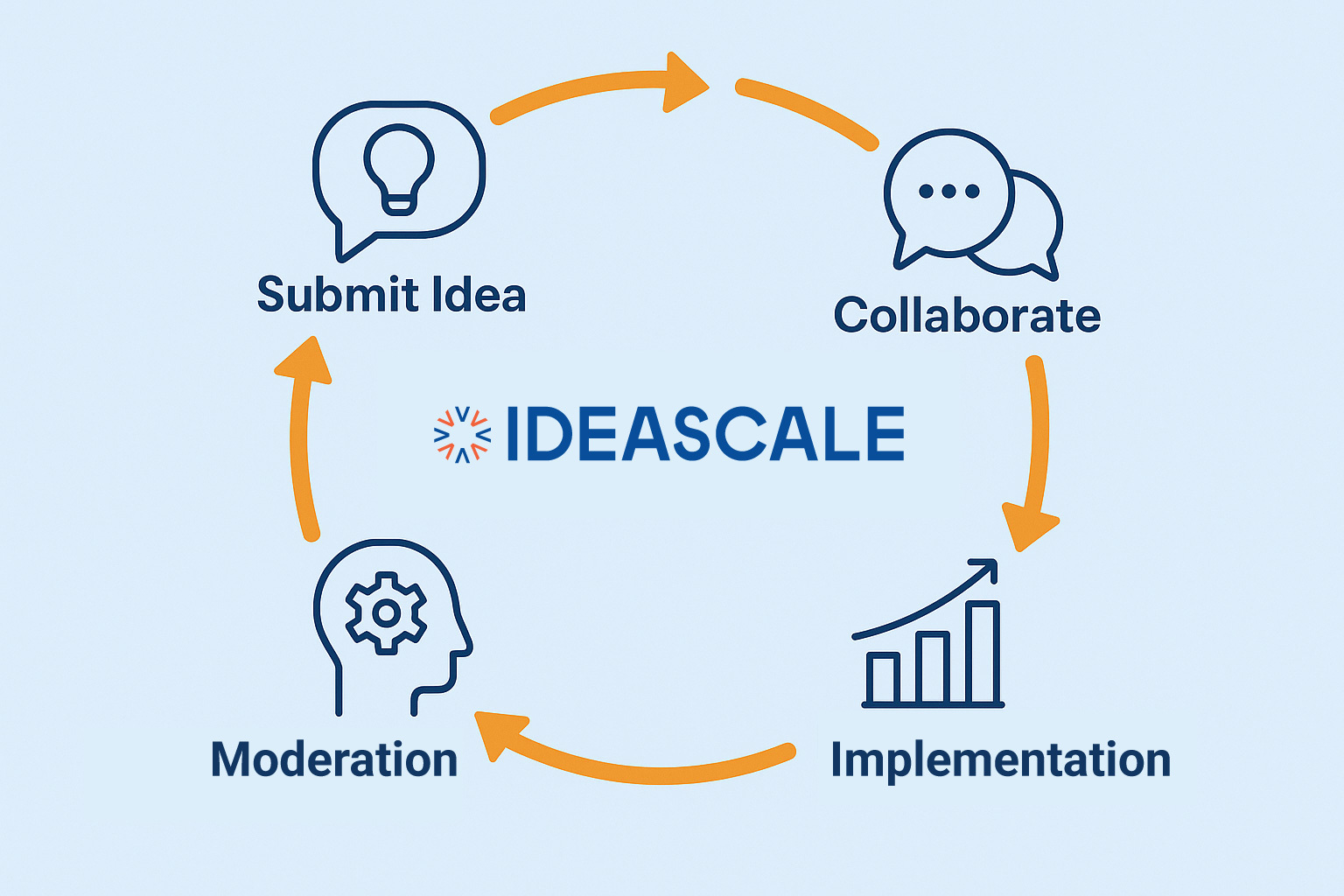

Consider this in the light of the knowledge, that society’s expectations of the government’s perceived scope and performance have only increased (see above). Recent examples include societal challenges such as the energy transition and other sustainability themes, for the Netherlands a desired shift towards a new governance culture, and tackling major societal problems such as demographics (ageing), shortages in the housing market, increased social inequality, accessibility of healthcare, the long-term approach to corona, emerging international and national security issues such as recently with Ukraine, a lingering undermining of the democratic rule of law by the impact of social media and populists, or digital privacy issues inside and outside government. This list is long, and is growing strongly rather than declining. In short: these unusual times bring with them unprecedented challenges, and require an organisation that continuously adapts to these new realities and is and remains innovation-ready. Unprecedented pressure requires unprecedented measures. Success in fulfilling the government’s social tasks is closely linked to being able and willing to systematically and structurally improve one’s own innovation capacity. The latter can be built with an innovation management maturity model, call it a reference model for improving innovation capability. Such a model upholds an ideal picture, and by holding up a mirror to people, it shows what steps you can take to achieve improvements. Because improving innovativeness mostly consists of a multitude of very small improvements, made in conjunction with each other.

Origins of the IMS-GOV innovation management maturity model

The first version of IMS-GOV was written by trial and error in the period 2008-2013, and a disproportionate number of development hours went into it. Innovation professionals would label these sunk costs, but that is a euphemism for what actually happened. The contribution of the two main authors, David Williams and Gert Staal, of the original maturity model started in parallel around 2008, as attempts to produce an innovation reference model based on experience in digital product development. It was through a chance contact through LinkedIN between Gert Staal and David Williams in 2011 that this initiative took more direction and focus, namely through the insight that the joint work they wrote contained core components of a reference model describing that ideal state which an organisation can move towards in terms of innovative capacity as described above.

David and Gert had met by chance through a discussion thread on LinkedIn and quickly set out on extensive digital transoceanic conversations about a wide range of topics in innovation capability. We had independently written components of this reference model, and we linked these components together, making it a concerted and comprehensive body of knowledge, and the constituent parts and documents still missing were completed and this new set was further developed into a comprehensive innovation reference model. We were supported in this process by an external committee of innovation experts and several panel sessions held with PDMA in the period 2011-2014. This set of documents and tools was formally adopted in 2013 by the Product Development and Management Association (PDMA), of which Gert Staal was already a member, and was on the international Board of Directors. The model itself was incorporated into a Dutch not-for-profit entity called the TIM Foundation, to ensure its continuity and allow the model to develop independently. Eventually, David and I decided to discontinue the agreement with PDMA at the end of 2018 as there was no future in the cooperation. The great advantage of this exercise, however, had been that, thanks to interaction with dozens of innovation experts from this international association, we now knew that the model as such had passed a substantive trial-by-fire and had stood its ground. From the experts’ point of view, there was no doubt about the validity of the content. Meanwhile, in several sessions with experts in the Netherlands and in Chicago (at PDMA), we trained dozens of consultants as certified innovation management assessors, from major reputable companies. This was a great experience and led to memorable discussions on the topic, which in turn led to adjustments on the original content.

The conversion project: towards a public reference model, IMS-GOV

Given its roots, the original model was very clearly written from the perspective of a for-profit organisation as its de-facto model, even though its applicability was thought to be universal by the authors, and it stated its origins as such. On reflection and in our discussion with the Dutch central government, it certainly turned out not to be directly applicable in a public or not-for-profit setting, especially when we wanted to deliver a version for the central government. Also, the working language of the original model was English, which is of course quite logical if you want to work with a Canadian, but impractical if you want to use it in a Dutch setting. First of all, the model was therefore converted from English to Dutch in its original form. We then took up the conversion challenge. A lot of its language was then made more neutral and universal for use with public, not-for-profit, and for-profit organisations alike. That turned out to be a very necessary intermediate step. Next, a lot of rebuilding was done on certain content segments:

- The sustainability guideline, previously sent along as a separate component, was integrated into the main work. After all: if a project today is not sustainable, can it actually be called innovative? The answer to this today is: an outright no. This was previously a source of debate because it could lead to exclusion, but this bridge has been taken.

- In addition, clauses have been included for e.g. core values (increasingly important today), and on the procurement of innovation projects in the setting of government and not-for-profit, and there has been further extensive tinkering with various sections.

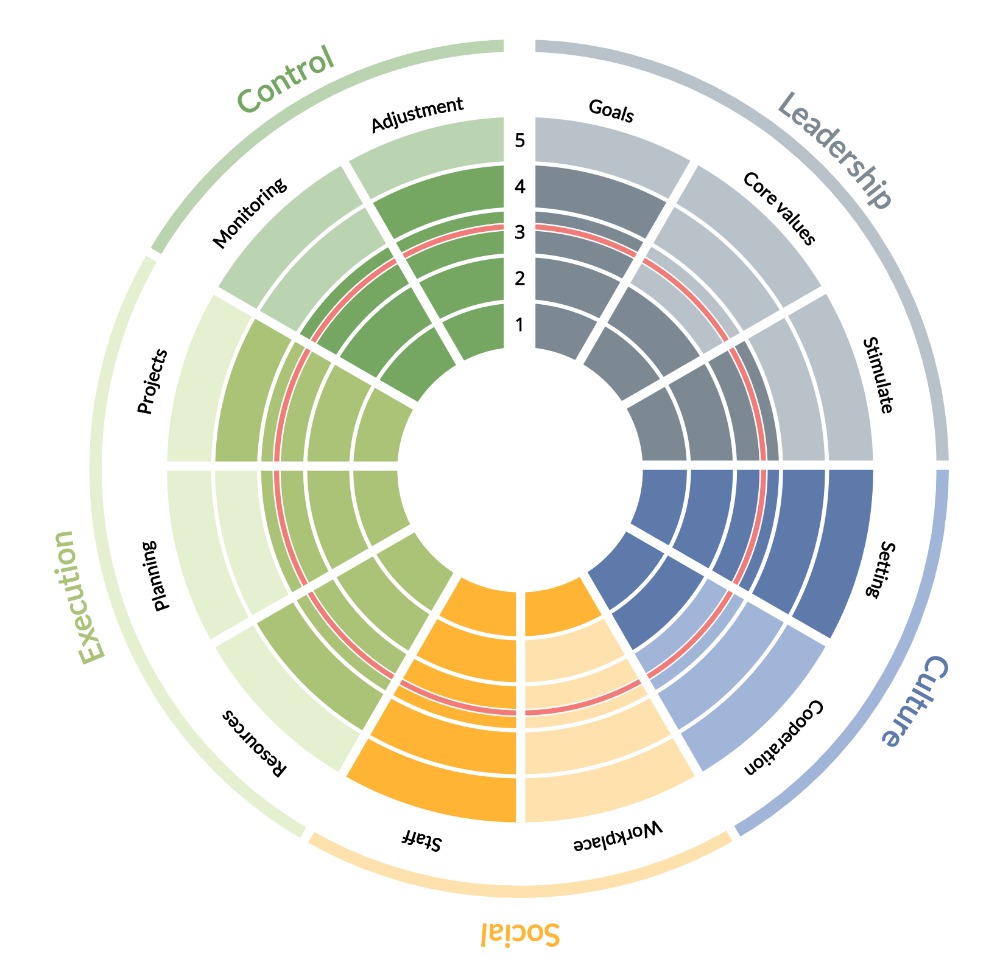

- The main structure (consisting of six segments in the original model: culture, leadership, resources, processes, check, improvement) has also been modified and converted to five: leadership, culture, social, implementation, improvement, with the last topic being a contraction of check and improvement.

- The questionnaires and other tools were also adapted to the new structure to make the whole thing consistent again. The latter in particular is a job not to be underestimated: if you pull a string of spaghetti anywhere in this model, the whole plate of spaghetti will shift.

- Following this, the original presentation material was also translated into Dutch, and adapted to the new structure.

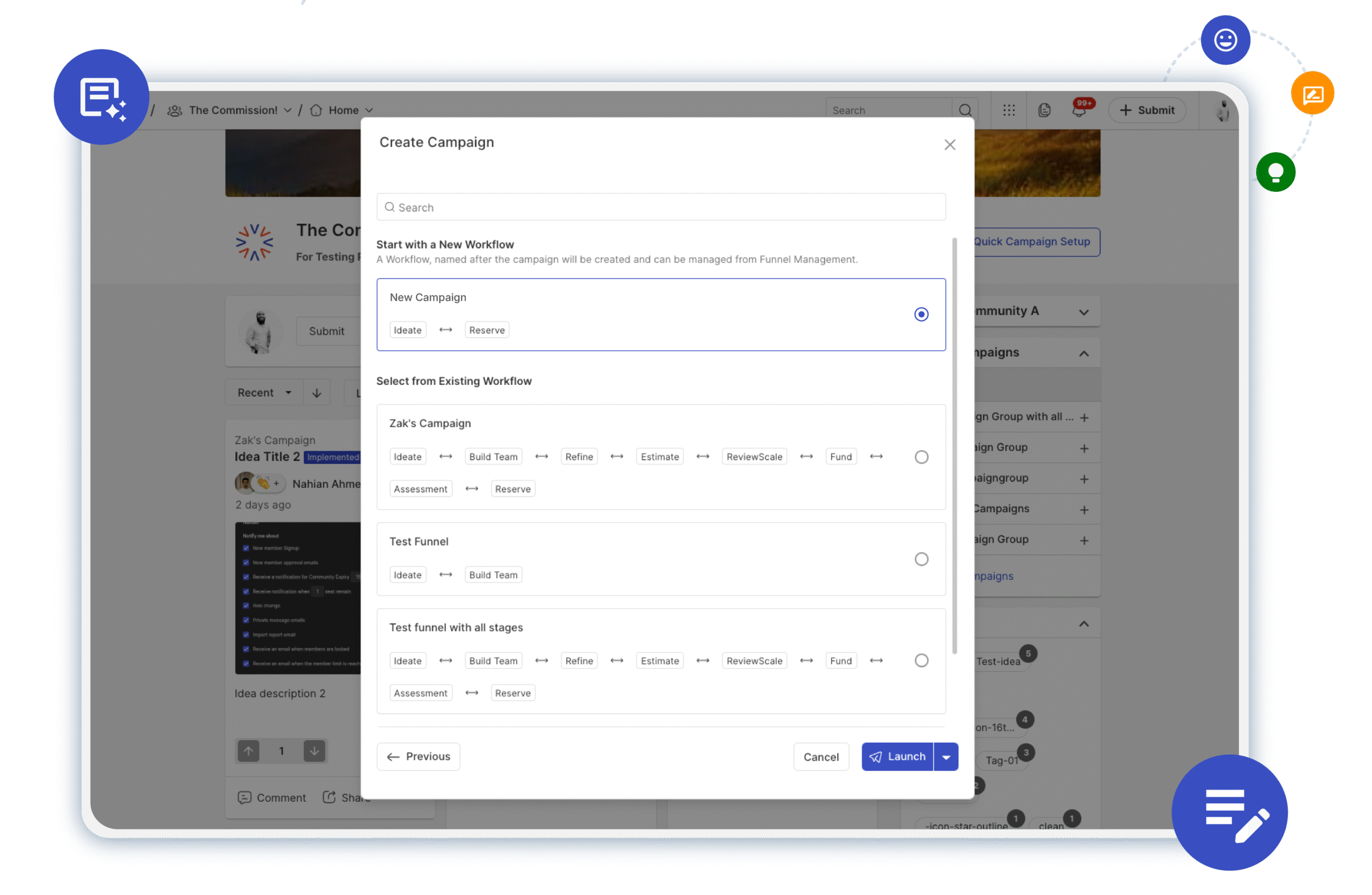

This conversion and adaptation process involved the better part of a year. A digital version of the innovation management scan, a tool that allows a quick look at an organisation’s innovation capability, was also created. The final model was christened IMS-GOV: Innovation Management System – Government version. At the end of this whole process, the result has been integrally translated back into English. We are happy that the model ‘stands’ again, in the form it now has, but improvements are always welcome. The model has the TIM Foundation as its home base for further development, and as a certification body for participants.

Finally we are going to train groups!

In the spring of 2020 (i.e. corona high tide), we started training a first group of around 25 innovation managers and consultants government-wide. As good and bad as it went under the circumstances, live sessions were held, again interspersed with online sessions, depending on the severity of the lockdown at the time. Participants came from many parts of the central government: Ministries of Justice and Security, Defence, Interior and Kingdom Relations UBR), but also from large government departments and independent public bodies such as the Tax and Customs Administration, Meteorological Service, and JUSTIS. The enthusiasm to start was very high: the training, organised by the Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, was almost immediately substantially oversubscribed. There was evidently a great need for this subject matter. Currently, we are in our fourth year of classes and the training is continually oversubscribed. We also started a new version for decentral governments and not-for-profits, as the original version was for public servants of the central government only.

Experiences of participants in the first three series of trainings

To ensure the privacy and safety of participants, strict confidentiality applies during the session: we applied the so-called Chatham House Rules. We learn a lot from each other, but this requires that everyone is invited to speak freely. This creates an environment where people can really learn from each other, and build a bond of mutual trust and a sense of belonging. We can draw the following key generic lessons, which repeatedly emerged among participants from the discussions:

- Culture, culture, and again: culture. Once again, it appears, that a culture that embraces innovation unconditionally is crucial for improving innovation power.

- Good leadership is crucial: without leaders who embrace, propagate and actively support innovation, any progress becomes difficult if not impossible.

- Rules and frameworks: do have them and sometimes consciously dare to let them go under controlled conditions. To be innovative, it is common knowledge that from time to time you have to consciously be willing and able to think outside established frameworks. However: a government organisation or not-for-profit also has its own operations, knows its own laws and rules that cannot be easily pushed aside simply because they are laid down in self-made laws and regulations. Finding the right balance between operational results and risk limitation on the one hand, and daring to take sufficient risks and show entrepreneurship on the other, is of great importance. Creating room for experimentation is an important condition in this respect.

- Time must be taken: it takes, we noticed, a lot of time and attention to explain the maturity model properly to people who have not yet worked with it. Some elements you had to repeat two or even three times. But the good news is: once the penny has dropped, you never get this systemic thinking out of your head, and from the philosophy of the model you can meet a lot of challenges, because they give you a starting point and a way of reasoning and iron logic in discussions with others that is so solid that it cannot be easily overturned.

- How then? Many questions that came to us related to the ‘how’: HOW do we do certain things, rather than the WHAT, the latter was very clear in many cases. This part will be deepened further. Indeed, it is clear that further guidance will be needed in this area. Context and explanation of the application of models and processes. Guidance on implementation of ‘jobs’.

- Conceptualisation is elementary: some terms and language around innovation management have yet to ‘set’: not for everything that has been covered are the right homegrown terms already available in the public and not-for-profit This is a matter of time.

- Money and commitment: investing in innovation is more than setting up an office in an old factory building, with a good coffee machine and big beanbags. Investing in innovation management is a long-term process and the commitment from leadership (not one leader, but leadership over years) that you need for success.

- Drop-in time. Participants can perform the (lighter) scan after about 10 sessions, but being able to undertake extensive assessments, still requires additional training and guidance (we have reworked this fact into an additional phase 2 for those interested in continuing with deeper innovation assessments).

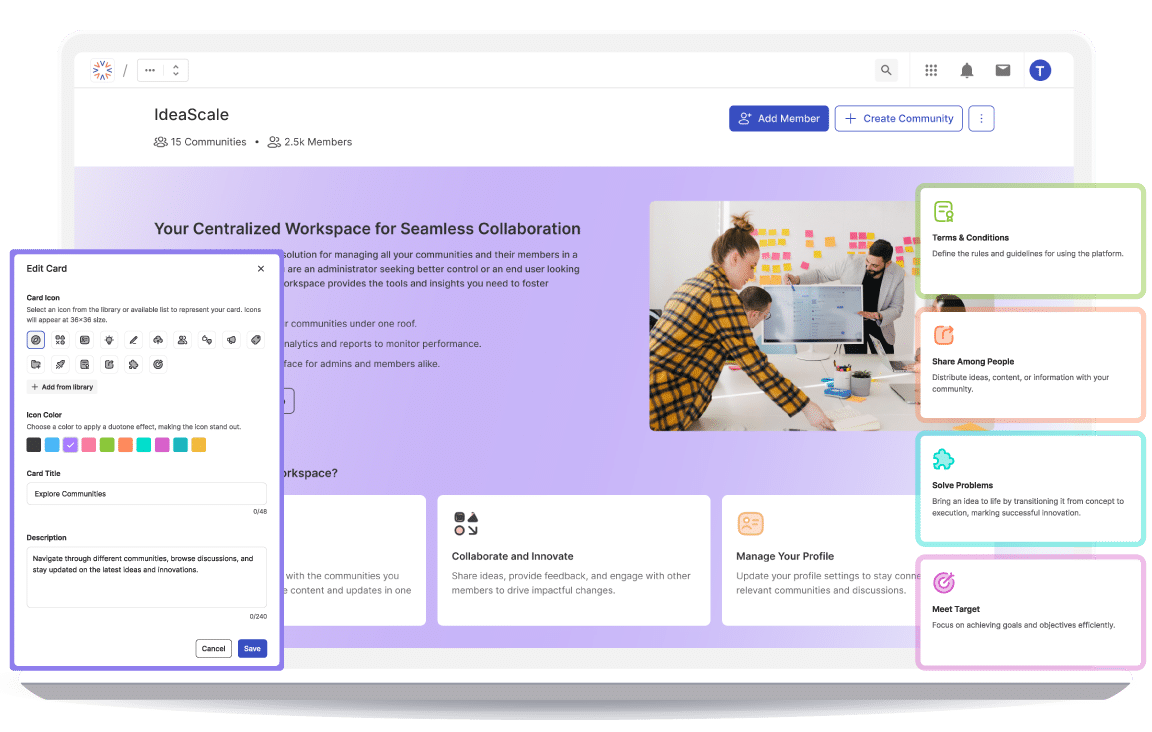

- Commit to a community. It is essential, that we continue to support participants after the session, coach them, provide them with relevant material, advise and assist them. This requires setting up a community toolkit or reusing or repositioning existing tools.

- ‘The government’ as an organisation does not exist at all. Yes, it is ‘many-headed’, i.e. with many manifestations, subcultures, work processes, identities, and the like. Providing good advice (by trainees) in this context is, and always will be, tailor-made for the organisation in question.

- The government’s role in innovations is very broad and different laws apply to each of these roles: from facilitator (create the right conditions for others to innovate), to innovative producer (build a new service, product or facility, e.g. a passport or a digital counter), to investor (put money into funds that invest in innovative projects (e.g. a Corona app). For each of these roles, it is of great importance, that you look again, whether you are in the right mode as a government: you should not want to be in a role as a product developer in a development process if you are actually in that context only a facilitator or a connector, to which other laws apply.

- There was great enthusiasm and warm interest. Discussions at the table were authentic and honest. Experiences were richly shared. Everyone experienced this as extremely valuable.

- Last but not least, never forget: you can do it yourself! As long as you keep taking the right decisions and steps using your own reference model, you don’t need an external advisor to tell you what to do. Continuing to build authentic innovativeness independently and on your own ability and insights with the help of your own trained consultants, or with the help of colleagues from e.g. UBR/IIR is many times more powerful than any outside intervention.

Conclusion

This is an evolving innovation management reference model, it will develop further over time. We have realised over time, that if we want to have a lasting effect on the government’s innovativeness, it will be a process of years before the desired effects become visible. We will have to build an internal community of experts for support and critical mass.

It was actually to be expected that this journey will take years. What is essential, however, is that the organisation maintains and continues to support such an initiative for a number of consecutive years, so that it matures and starts to have an effect. In this way, we are going to give the innovative power of the government and public institutions a firm push in the right direction, from within. There is no shortage of interest and goodwill!

Gert Staal, Chair and managing director, TIM Foundation, a Dutch not-for-profit organisation.

For more information about the Foundation and the maturity model, contact Gert Staal at gstaal@timfoundation.org or on +31 6 2037 1093.

Most Recent Posts

Explore the latest innovation insights and trends with our recent blog posts.