Thinking Together is the Ultimate Core Competency

Pick an industry. Any industry. In nearly every case, you’ll find two companies that started at about the same time, with roughly the same resources. One of them succeeds and the other fails. Or one prospers while the other languishes. Why? Ask ten people and you’ll get as many answers. But in the end, their answers come down to this—the successful company out-thought its competitor, which means that thinking is the ultimate core competency.

Actually, thinking together is the ultimate core competency. Most good ideas are produced by groups of people thinking in concert. Contrary to conventional wisdom, innovation is more often a social affair than an individual act.

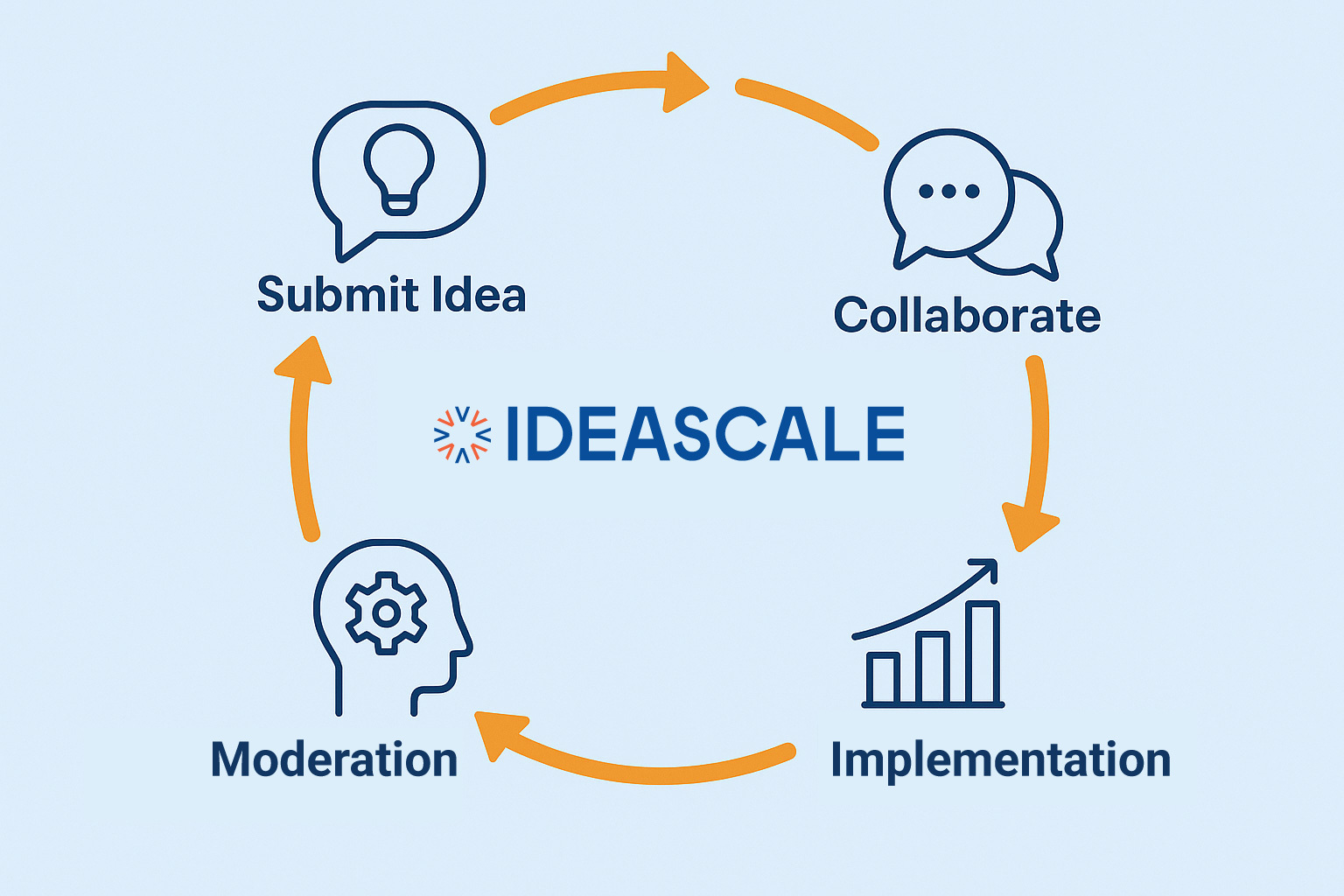

How do groups go about thinking together? They engage in conversation. They think out loud. Like most things, there’s more to conversation than meets the eye (or ear). And like most activities, it’s something that can be done well or badly.

One way to classify conversations is by purpose. Three of the most common purposes are to describe, explain, and prescribe:

- Describe: Sometimes the purpose of a conversation is to describe what was, is, or will be the case. For example, a group of managers might note that business was down by 10 percent last year (was the case), or that it is down 10 percent this year (is the case), or that they expect it to be down 10 percent next year (will be the case).

- Explain: Explanation usually follows description. Once some phenomenon is described, people want to explain why it happened, is happening, or will happen. The conversation turns to identifying causes. The cause of the business decline, for example, might be the entry of a new competitor in the market.

- Prescribe: Prescription follows explanation. After the causes are understood, the group will talk about ways to act on the causes. In the example, the managers might decide to lower prices to force the new competitor to exit the market.

The elements of a conversation are topic, issue, position, and argument. Groups are frequently overwhelmed by the task of keeping track of the elements. As explained in my post titled “Conversation Mapping,” tools for diagramming a conversation can help. But while a conversation mapping tool can help a group do a better job of thinking together, it can take them only so far. The method they use to converse will take them much further down the road. Two of these methods are advocacy and inquiry.

Advocacy is the practice of debate. With this approach, a person adopts a position and advocates it to the exclusion of all others. Advocacy is the predominant form of conversation in American culture. Nearly everywhere you look—on the editorial page of the newspaper, in the courtroom, on TV talk shows, in the company boardroom, even the sidewalk cafe— you find people zealously clinging to their version of the world. It reminds me of the pro-gun bumper sticker: “The only way you’ll take my gun [position] away from me is to pry my cold, dead fingers off the barrel [argument].”

Inquiry is the practice of listening and understanding. Rather than maintaining a death grip on their position, each group member works to understand the positions of the other members. To understand does not necessarily mean to agree. It simply means suspending judgment and listening without resistance to another’s point of view. Few of us really make the effort to listen deeply. As one wit put it, “People don’t listen, they reload.”

Advertising executive Byron Nahser tells of a time when he was forced to engage in inquiry. Nahser attended a conference at the University of Chicago led by M. Scott Peck. The attendees were divided into small groups, each group was given a problem to solve, and they were required to use the following ground rules: 1) When a person has the floor, you cannot interrupt or correct him, 2) If you want to challenge a person, you can only say, “I hear you saying . . . .”, and 3) You can respond only when the other person is satisfied that you heard and understood what he had to say.

Nahser’s first thought was to bolt for the door, but, he says, “I stayed put, wondering if Milton Friedman would suddenly appear to stop all this nonsense.” Over the course of three days, the group went through four stages. First was the strained conviviality and role-playing of a pseudo-community, which, he comments, “[Was] familiar to those of us in business, since American corporations operate at the pseudo-community level . . . .” The next stage was chaos, as conflicting positions emerged and subgroups formed to defend them. The third stage was emptying. The participants began to empty themselves of old beliefs and started listening to one another. Finally, there was the stage of real community. The group became a community of inquiry in which, Nahser explains, “Each person add[ed] ideas, insights, or ‘a piece of the truth,’ building toward a clearer picture of reality from which flow[ed] the decision and action.”

When a group is thinking together, they act as if the group is a single, intelligent organism working with one mind. When done well, the group produces an idea that no one person could have thought of alone. Unfortunately, thinking together can be done well or badly (or not at all). Like singing together, thinking in concert is a learned skill. That it is the ultimate core competency, as I said at the start, suggests that it is a skill worth learning.

Most Recent Posts

Explore the latest innovation insights and trends with our recent blog posts.