This post is about a meeting method variously referred to as conversation mapping, dialogue mapping, or argument mapping and a software tool that supports it. Conversation mapping is the outgrowth of Issue-Based Information Systems (IBIS), an idea first proposed in 1970 by Horst Rittel, an urban planner and designer. Rittel’s idea was to design an information system that supports group problem-solving. He was particularly interested in devising a way to attack ill-defined problems, which he called wicked problems, where the number and nature of the issues is ill-understood. The central elements of IBIS are topics, issues, positions, and arguments (which I prefer to call reasons). To start, let’s take a closer look at each of these elements.

We sometimes use the phrases topic of discussion or topic of conversation. Intuitively, we understand the term topic to mean what is being talked about or the aboutness of some stretch of dialogue. Lengthy dialogues typically have multiple topics and sub-topics. In a casual conversation the topics are unplanned and unpredictable. After the fact, you could describe the “aboutness” of a casual conversation in terms of a hierarchical framework of topics and sub-topics, but prior to the conversation you would have no way of knowing what it will be about. This contrasts with a formal, task-oriented dialogue, such as a strategic planning session, in which the topical framework is pre-planned and imposed on the participants. But even formal conversations veer into the unplanned and unpredictable. People introduce new, relevant topics or wander off-topic into irrelevancies, making it difficult for the participants to keep track of what they’re talking about. Even harder to track are dialogues having to do with wicked problems, which often start with no more topical structure than a trigger phrase like “the employee turnover problem,” “the financing problem,” or “the crime problem.”

Oftentimes, as people talk about topics, issues are brought up and disputed. An issue is a point of controversy that is best stated in the form of a question. One way of classifying issues is to say that there are two types—descriptive and prescriptive. Descriptive issues involve questions about what was, is, or will be the case. In other words, the questions ask for a description of some past, present, or future thing. Examples are: What caused our revenue to decrease last year? Does more advertising always result in an increase in revenue? What will our revenue be next year? Prescriptive issues involve “ought” or “should” questions about the past, present, or future. In other words, the questions ask what should have been prescribed or what should be prescribed, now or in the future. Examples are: Should we have increased our advertising budget last year? Should we maintain the current advertising budget? Should we increase the advertising budget next year?

It’s usually the case that people have different positions on an issue. (More formal terms for position are assertion, claim, and conclusion and less formal are the terms idea, proposal, and alternative.) One way of defining position is to say that it is a statement that a person wants others to believe. Another way is to say that a position is a descriptive or prescriptive answer to an issue question. A useful metaphor for understanding issues and positions is to imagine an issue as the point at which there is a fork in the road (conversation). One person holds to the position that “this road” is the right or best way forward, i.e., that his description or prescription is the right one or the best one. Another person takes the position that “that road” is the correct or superior route, and perhaps others conclude that a third or fourth road is the way to go. For example, in response to the question (issue) “Should we maintain the current advertising budget?” one person may hold to the position that it should be decreased, a second that it should remain the same, and a third that it should be increased.

People usually cite one or more reasons for their position. (Equivalent terms are argument, premise, and case.) A reason is an explanation or rationale for why someone should believe that a position is right, correct, or appropriate. Oftentimes, a position and a reason-for are packaged in the same sentence, as happens when someone says, “I think we should do X because Y.” A person may also present reasons against a position, such as when a person says, “I don’t think we should do X because Z.” In both cases, the people are reasoning, which has the general structure of I think this because of that.

There are many different kinds of reasons—some valid and some invalid, some better and some worse—and there are valid and invalid ways of reasoning. We won’t get into all that here, other than to say that many reasons are statements that present information, or evidence, such as relevant facts, examples, and statistics. For example, a person promoting the position that his company should increase its advertising budget might cite reasons like a) we increased our advertising budget last year and sales increased substantially (a relevant fact), b) the Widget Company increased their ad budget and their sales improved significantly (anecdotal evidence), and c) industry research demonstrates that in 90 percent of the cases, the benefits of advertising outweigh the costs (statistical evidence).

To summarize, conversations develop around a framework of topics and subtopics. As people talk about the topics, issues may be brought up and disputed. Descriptive issues take the general form: What was, is, or will be the case? Prescriptive issues take the general form: What ought to be the case? People often take different positions on an issue. They usually cite reasons for their position and may also present reasons against another person’s position. Whether for or against, a common type of reason is evidence.

The foregoing paragraph paints a nice, tidy picture of conversation. In practice, nothing could be further from the truth. Real conversations are messy. People jump ahead, or back, or otherwise hopscotch through the topics, or they digress and stray off on tangents. They may fail to identify the issues or do a poor job of articulating the ones that are identified, most often by presenting the issue as a controversial statement rather than converting it to a question. People frequently state their positions in an ambiguous way and it isn’t always clear which issue the position is connected to. They may also cite poor or invalid reasons for or against a position, if they cite any reasons at all. In group discussions these problems are compounded by the sheer volume of the topics, issues, positions, and reasons that people need to keep track of.

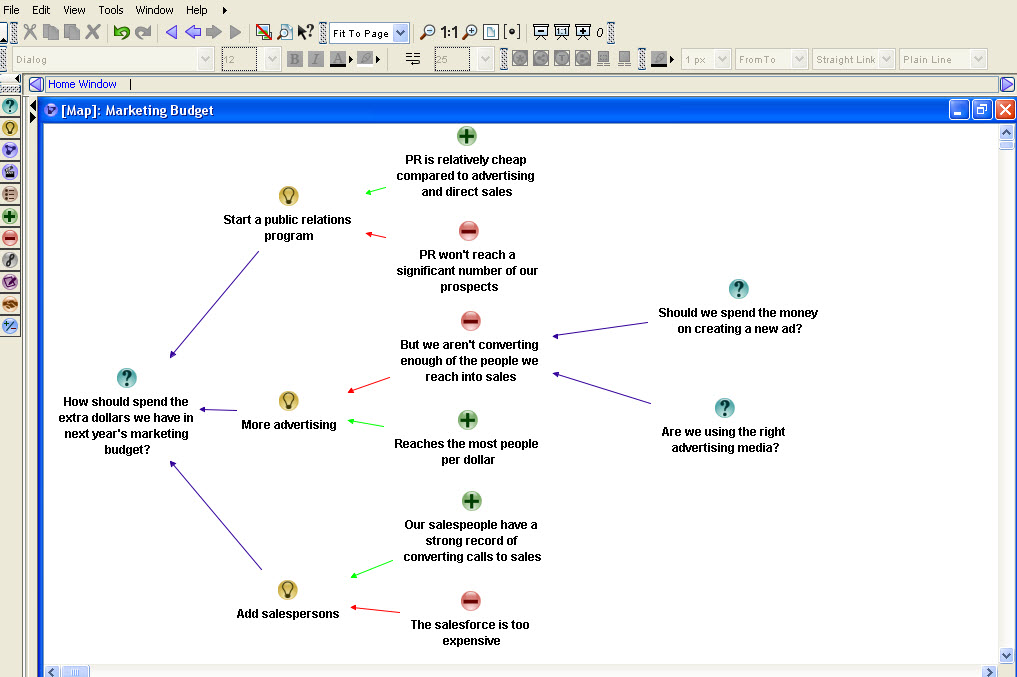

Conversation mapping is an effective way to manage messy, voluminous group discussions. While it’s possible to do it on a whiteboard, using a projector to display a dialogue mapping software is far more effective. Compendium (Home · CompendiumNG/CompendiumNG Wiki · GitHub) is the de facto standard when it comes to dialogue mapping tools. As shown in the screenshot, an entire window is dedicated to a particular topic or subtopic (in the example, the marketing budget) and a master window is used to tie the topic framework together. A question mark designates an issue, a light bulb a position, a plus sign a reason-for, and a minus sign a reason-against. Compendium employs a few other icons, such as a reference icon for storing reference documents, but the question mark, light bulb, plus sign, and minus sign are the core icons.

A Compendium discussion typically starts with a root issue on the left and “unfolds” from left to right as people add positions and reasons. The left-pointing arrows designate that one item responds to another. Whereas a position always responds to an issue and a reason always responds to a position, an issue can be raised with respect to any item on the map. (Note, for example, the two issues that respond to one of the reasons-against in the screenshot.) In this way, Compendium implements the Issue-Based Information System that Rittel envisioned some fifty years ago and, more importantly, a method for unearthing the many issues that lay buried when a group first confronts a complex problem. Depending on the level of complexity, a Compendium map can run to dozens, hundreds, and even thousands of nodes. It’s been used for everything from strategic planning sessions to complex technical problems.

At first glance, Compendium may strike you as a very simple, almost toyish, software tool. But don’t be fooled. Its easy-to-use interface hides the complexity of the hypertext engine that drives the software. Hyperlinks are created by copying and pasting a node from one map to another. Another feature is a contents window that enables users to enter additional information about each node—such as a piece of text that elaborates on the nature of an issue or an extended explanation of a reason—and the nodes and their contents can later be “morphed” into a written document. Compendium also includes a search engine for finding and displaying nodes that have been tagged with a particular keyword.

Using Compendium to facilitate a group discussion is like being a translator. It requires that you translate people’s natural language into the topic-issue-position-reason language of Compendium. The hard part is learning to tease these four elements out of everyday speech—for example, converting controversial statements into issues phrased as questions, separating positions and reasons that are packaged in the same sentence, and tracking conversational exchanges that are embedded within other exchanges. Learning to translate requires many hours of practice, but it’s worth all the work, for dialogue mapping is an excellent way to improve the collective thinking of a group.

I’ll end this post by relating it to a few of the other posts on this blog and then give you a thought to think about:

In the article Collaboration and Shared Space, I explained that collaboration requires shared space—a space, such as a flip chart or whiteboard, where collaborators are able to share their thoughts. With the advent of projectors, shared space now includes shared displays which, in turn, make it possible for groups to think through new groupware technologies, such as Compendium.

In the article What is Thinking?, I explained that to think is to link. More to the point, to think is to link one idea to another so as to arrive at some conclusion (position) about the world, which is precisely what’s going on in a Compendium map.

In the article Where is Thinking?, I explained that our thinking is augmented by the technologies that we think through. By thinking through pen-and-paper technology, for example, we are able to accomplish cognitive tasks that we would otherwise be unable to do, such as multiplying two large numbers and linking together a long chain of thought. Like other groupware tools, Compendium is a technology for a group to inter-think through. By inter-thinking through the software, a group is able to accomplish a cognitive task that it would otherwise be unable to do—link the group members’ ideas together to build a large structure of thought. In this way, Compendium augments the collective thought and intelligence of the group.

If you spend a few moments thinking about what I’ve just said, you’ll begin to see the enormous potential of groupware tools. And that’s a thought worth thinking about.

Most Recent Posts

Explore the latest innovation insights and trends with our recent blog posts.